An art combined with an alchemical skill borne of sensorial sensitivity, the creation of perfume is a mastery of intuitive matters; yet it is also a craft rooted in the intellectual mind and reason. The formulations of Mathilde Laurent, Cartier’s in-house perfumer, are a combination of precise science blended with a sacred reverence for the olfactory art. Deciphering this ephemeral language is a tricky feat. In an attempt to do just that, we set out to gather insight on whether there is a universality to feelings of love, emotion, memory, and other subjective internal realities, when the brain’s neurons are triggered by smell. We enlisted the expertise of neuroscientist and spiritual thinker Dr. Tara Swart, and asked the two specialists to confer on the individual experience of consciousness and nature, when it is inhaled through the nose.

Tara: We are trying to connect the sense of smell to emotion, memory and love—If you smell something that you really love it often brings a memory, right up to the front of your brain. What we know is that smell between two people in a romantic relationship is the most important sense, it’s the only one that can’t be wrong.

The olfactory bulb comes out to the top of your nose and there’s only a very short connection until it goes to the part of the brain where smell is mediated. That’s in the limbic system, which is the emotional and intuitive part of the brain. Smell, emotion and memory, are very strongly connected.

You can love somebody even if they don’t look how you would like them to, you can love somebody if you don’t like their voice, but if you don’t like the smell of the person you can’t be compatible in a romantic relationship.

Mathilde: In my work and what I observe in humans, reason always comes back and influences everything. As a perfumer, through reason, you overcome the instinctual reaction you may have to a smell. A perfumer’s expertise is to objectify a smell. I am very sensitive, I can be easily overcome by emotion—but as far as smells are concerned, I can’t be overcome as easily in comparison to my other senses.

Tara: Is that because your job is to create smells that have an emotional impact for other people, so you have to remove your emotion?

Mathilde: In my work, one has to objectify all smells because the creation of perfume is very close to making art. In art, the ingredients like paint, have to be an objective tool, just as notes have to be tools used in music, it’s the same for smells as far as creating perfumes. When we try to create a perfume, what we’re looking is to create a certain aesthetic and beauty—and maybe that will or will not move people—but we can never predict nor know others’ emotional reactions. Emotions are unique to each and every individual. Memory, emotions and smells are so closely interlinked, that when you take a smell, like for example rose—some will love it because it reminds them of their grandmother’s garden while others will absolutely detest it, because it triggers memories of being spanked for breaking a rose from the same garden. So for the same ingredient each person will have a different emotional reaction—a very positive or negative response—it is variable. In perfumery, you can’t say all flowers smell lovely, because for some people certain flowers smell of sadness, or smell of fear.

Tara: I’m really interested to hear from you about what’s considered to be masculine or feminine? Perfume used to be traditionally either for men or for women, and then there was more of a unisex type of perfume, and personally I often like perfumes that were meant to be for men. How does that play into your decision making when creating?

However if we are speaking about smells of nature, and materials from nature, then for most people, the smells are the same and so they can actually make up a certain language.

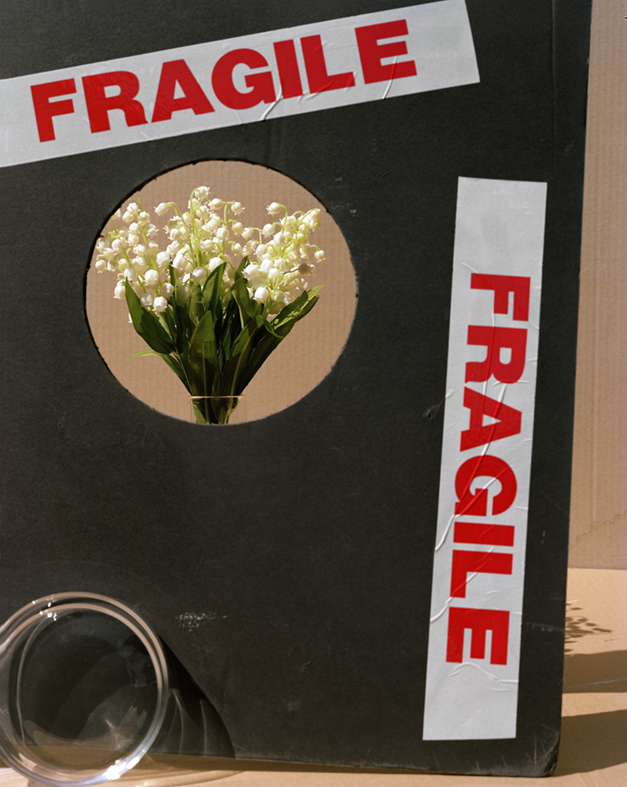

Mathilde: Smells have no gender. We always think flowers are feminine, but in fact they are hermaphrodite/ intersex—if they have reproductive organs they are neither just masculine or just feminine.

When we look at antiquity, if we look at the Middle Ages, up until the Second World War—there was no sorting between the genders— the only differential was between the kings/divinities and the people. Thankfully nature offers her bounties to everyone.

Tara: Lots of people are asking me now, what are the 2020s going to be like after this pandemic—I think it will be like the roaring 20s of the 1920s, and I just wonder if there are any perfume trends that go along with the mood of the world?

Mathilde: I hope that we’ll have a new roaring 20s, literally mad. It will be with a great deal of pleasure. What I feel as far as the pandemic is concerned, and I think it’s absolutely fascinating, I feel the pandemic has placed our olfactory sense to the forefront.

Tara: I was just about to say that.

Mathilde: At the beginning of the pandemic, it was really interesting to see how everybody couldn’t care less about losing their sense of smell. When they saw a person close to them lose their sense of smell, they would then realize, they’ve also lost their sense of taste. In French, we say avoir goût à la vie—to have a taste for life, se sentir vivant—to feel alive. (In French the verb sentir is both to feel, and to smell.) If you can smell the odors of life, then you are alive; if you cannot, well, then you are dead.

Tara: Now that we have understood that losing our sense of smell is something to be feared, it’s quite interesting for me to think about what you’ve said in terms of how people think smell is invisible—but it’s actually particles that go into your nose and release this cascade of chemicals like dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins and that’s what gives us the feelings.

Mathilde: Is oxytocin created through emotion through memories, which are attached to smells, or is it something molecular?

Tara: The neuroscience research shows us now that we can scan brains and bodies, that the molecular effect is very much aligned and correlated to emotions, memories, feelings, even the way that we think—so it’s kind of both.

A classic example of this is with children, who used to get carsick, hate the smell of petrol; but some people love the smell of diesel and gasoline. I used to get carsick and I feel like vomiting (when I smell petrol). But there are some trends, where kind of everybody says yes, I really like that—like the smell of baking because it reminds them of being in their grandparents’ or their parents’ home. The smell of fresh cut grass and my favorite is the smell of fresh rain on the earth.

Mathilde: I know the name of this molecule, it is geosmin—it is released in the air, when rain falls on the soil. I love this molecule—but when you smell it in a laboratory, it’s very concentrated, very strong, it’s like raw beetroot. The earth smells of what’s growing into in it, so in fact it’s the beetroot that’s giving the earth its smell.

Tara: The beetroot is red and that goes with the root chakra which is your earthing and grounding isn’t it so? And the color of the Cartier boxes.

Mathilde: That’s an amazing connection, I love it. The fact that the beetroot grows in the earth and the earth smells of the beetroot is universal. In perfumery emotions to smells are unique to the individual, however nature is the universal dictionary of olfaction. This is why I don’t work with emotions—because I can’t envisage them, I can’t foresee them, I can’t predict them—there’s no universality in emotion, including olfactory emotions. However if we are speaking about smells of nature, and materials from nature, then for most people, the smells are the same and so they can actually make up a certain language.

Tara: I like to connect everything to evolution, because a lot of neuroscience can be explained by how our brains were shaped and molded over time. And because we were tribal people and we lived very much in keeping with nature and the earth. I wonder if there are some smells that are so primal like the earth or beetroot that it creates this universal connection? I want to tell you about a neuroscience experiment that I think you’ll like: if you’re ever giving a lecture in a room with over one hundred people, and you ask everybody to turn to the person next to them, to introduce themselves and shake hands, you will notice that within one minute 75% of people in the room will put their hand up to their nose. We basically do still smell each other, like animals but we’re not aware of it.

Mathilde: I love that, it’s wonderful. The intuition of it, as we have lost this use, and it’s fascinating to understand that it still exists. It’s totally unconscious.

Tara: But that only happens if it’s with somebody that’s a stranger. If it’s somebody that you know, then you don’t do it. It’s like a test to see if that person is part of our same tribe, someone familiar.

Smell was actually one of the most important senses to our survival because food was scarce, and we had to be able to feel and describe it if we found food. But if it was meat that was a bit old, and it had been out, we had to have that sense of disgust and that came from our smell.

Mathilde: Yes and we had to have that memory. When the meat was not good, you had to have a feeling of disgust, because in fact you reciprocate that smell with a sudden illness that you previously encountered. In fact it’s something that perfumers learned very quickly, because that allows them to work out how they can actually technically work using their nose.

I spend my life explaining to people why they can only smell their perfume for about three days. It is because you only get that alert once— and when you wear a perfume daily, the nose no longer feels that it needs to be alerted because, after all, it recognizes it as a perfume that you wear every single day.

Tara: Because the brain is always looking out for threats, and the brain filters out information while prioritizing what you need to thrive and that’s why we don’t feel the clothes on our body all day, because that would be a waste of brain power.

Mathilde: And it’s really important that perfumers know exactly how that nose functions because they are the intermediaries between the public and the science.

Tara: Absolutely.

Dr. Tara Swart is a neuroscientist, medical doctor, senior lecturer at MIT Sloan and author of bestseller The Source, which has been translated into 36 languages. Tara believes in the merging of science and spirituality to manifest your best life. @drtaraswart

Smells have no gender.

We always think flowers

are feminine, but in fact they

are hermaphrodite/intersex—if they have

reproductive organs they are neither

just masculine nor just feminine.